The following article on “Age of Brahma & The age of the Universe” is a continuation from the previous article: “Age of Brahma & The age of the Universe – 102“. Prioritize reading the previous article before proceeding to this one. Let’s try to separate the contents presented in a table from the previous article into individual parts.

Santana Dharma, with its vast spectrum of deities and spiritual practices, finds philosophical cohesion in the idea of the Trimurti — a trinity that symbolizes the three core aspects of the Supreme Consciousness. While representations of this sacred triad appear in Hindu scriptures, artwork, and ritual chants, the Trimurti is not just a mythological motif. It is, more profoundly, a metaphysical symbol that speaks to the underlying principles governing existence itself: creation, sustenance, and dissolution.

The term Trimurti, which literally means “three forms,” refers to the divine functions personified by Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva — the creators, preservers, and transformers of the cosmos. Each deity embodies a universal force:

- Brahma, the generator, represents the energy of creation.

- Vishnu, the protector, stands for preservation and continuity.

- Shiva, the transformer, is associated with destruction and transformation, which ultimately paves the way for renewal.

These divine aspects are not simply mythic characters but reflect the natural rhythm of life: birth, growth, and death. They remind us that the universe is in a constant state of flux, governed by cyclical patterns. In this light, the Trimurti becomes a philosophical model that connects cosmic principles to everyday human experience.

Interestingly, parallels are often drawn between the Trimurti and the Christian Trinity — the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. While both traditions articulate the idea of a divine triad, their theological interpretations and spiritual implications differ significantly. The Hindu Trimurti emphasizes processes of the universe as divine forces, whereas the Christian Trinity centers on relationships within the Godhead and their manifestation in human salvation.

These divine roles also align with the three gunas, or essential qualities described in the Bhagavad Gita:

- Rajas (Passion) – Embodied by Brahma, representing the force of creation and desire.

- Sattva (Purity) – Embodied by Vishnu, reflecting balance, preservation, and compassion.

- Taamasa (Inertia) – Embodied by Shiva, symbolizing destruction, darkness, and dissolution.

Beyond elemental and philosophical representations, the Trimurti also corresponds to different layers of consciousness:

- On the physical plane, Brahma reflects the psychic energy, Vishnu the mental faculties, and Shiva the physical essence.

- On the mental plane, Brahma symbolizes creative thought, Vishnu represents analytical intelligence, and Shiva governs emotions and intuition.

- On the cosmic plane, Brahma aligns with the Sky, Vishnu with the Sun, and Shiva with the Moon, each influencing the earthly realm in unique ways.

The influence of the Hindu Trinity extends into the four stages of human life, known as the Ashramas in Vedic tradition:

- Brahmacharya (Student Life) – Represented by Brahma, this phase is dedicated to learning and self-discipline. Here, knowledge is paramount, personified by Goddess Saraswati, the divine consort of Brahma.

- Grihastha (Householder Life) – Symbolized by Vishnu, this stage is focused on family responsibilities, wealth generation, and social duty. Goddess Lakshmi, Vishnu’s consort and the deity of prosperity, becomes the guiding force.

- Vanaprastha (Retirement/Forest Dweller Stage) – Represented by Shiva, this phase marks a gradual withdrawal from material life in pursuit of spiritual growth. Traditionally, individuals would renounce worldly comforts and embrace simplicity, echoing Shiva’s ascetic lifestyle.

- Sannyasa (Renunciation) – The final stage involves total detachment from worldly ties, seeking union with the Supreme Consciousness—Ishwara. At this point, the individual transcends ego and identity, and the couple (if together) dedicates life to meditation and spiritual liberation. The Universal Mother, as the consort of Ishwara, symbolizes the ultimate feminine energy.

Brahma – The Timeless Seed of Creation

In the vast tapestry of Sanatana Dharma, the concept of Brahma occupies a foundational yet often overlooked corner. Revered as the Creator in the cosmic trinity, Brahma’s origin and role are far more nuanced than a simple deity of genesis. Unlike widely worshipped forms like Vishnu and Shiva, Brahma’s legend spans metaphysical concepts, philosophical archetypes, and poetic symbolism that transcends mythology.

He is not merely a god with a crown of scriptures — Brahma is the first whisper of Consciousness forming into form. The Vedas, Upanishads, and Puranas refer to him in myriad ways: Om, the primal sound; Swayambhu, the self-born; Hiranyagarbha, the golden womb; Prajapati, the father of creation; Lokesha, the lord of realms; and Viswakarma, the cosmic engineer. Each name reflects a layer of cosmic function or philosophical abstraction.

The Womb of the Universe: Mythic Origins

In ancient cosmological texts, Brahma does not simply ‘appear’ — he unfolds. In one account, Brahman, the eternal formless reality, creates water and deposits a seed in it. That seed becomes a golden egg — the Hiranyagarbha — from which Brahma emerges. His watery birth earns him the title Kanja, the water-born.

Another poetic portrayal from the Mahabharata describes Brahma emerging from a thousand-petaled lotus blooming from Vishnu’s navel, earning him the name Nabhija (navel-born). This birth imagery places him not at the top of a divine hierarchy but as an emanation—an impulse—from a greater, all-pervasive Consciousness.

Some versions connect his birth to Maya, the Supreme’s creative energy. Maya acts as the womb of illusion and separation, allowing Brahma to manifest the illusionary yet structured world we live in.

Time: Measured in the Breath of Brahma

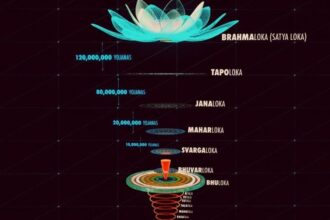

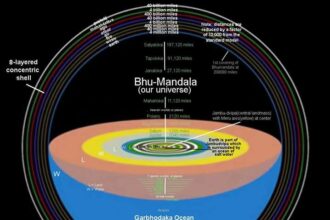

Hindu cosmology treats time not as a linear string but as cyclical oceans, and Brahma is the cosmic timekeeper. One day of Brahma (Kalpa) equals 4.32 billion human years, containing a thousand Mahayugas—each Mahayuga being a set of four distinct Yugas:

- Satya Yuga – 1,728,000 years

- Treta Yuga – 1,296,000 years

- Dvapara Yuga – 864,000 years

- Kali Yuga – 432,000 years

The night of Brahma lasts equally long, during which all creation dissolves into the causal sea — a phase called Pralaya. This rhythmic pulsation continues for 100 Brahma years, amounting to an unimaginable 311 trillion human years, after which even Brahma dissolves back into Brahman.

The Mind-Sons and Cosmic Delegation

Creation wasn’t Brahma’s solo act. From his mental faculties, he created Manasaputras — ten mind-born sons including Marichi, Atri, Angiras, and Bhrigu. These cosmic progenitors, alongside the Saptarishis (seven sages), were tasked with shaping galaxies, life forms, and cosmic laws.

Brahma also devised the Manus, the archetypal humans who ruled over vast epochs, ensuring civilization evolved in harmony with dharma.

The Four Faces of Cosmic Knowledge

In his divine form, Brahma is portrayed with four heads — a symbol of all-seeing awareness. These heads represent:

- The four Vedas (Ideally it is three) : Rig, Yajur, Sama, and Atharva

- The four Yugas : Satya, Treta, Dvapara, Kali

- The four Varnas (Its a system, not caste) : Brahmana, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra

Each varna is said to have emerged from different parts of Brahma’s body — head, arms, thighs, and feet respectively — a poetic metaphor for the functions within society.

Originally, Brahma was said to have had five heads. The fifth, looking upward, was severed by Shiva due to a legend involving Brahma’s obsessive gaze upon Satarupa, his female counterpart. This story contributes to why Brahma is rarely worshipped today.

The Divine Justice of the Swan

Brahma rides the Hamsa, a divine swan said to possess the unique ability to separate milk from water — a metaphor for discerning truth from illusion. This symbolizes the necessity for wisdom, purity, and discretion — especially for the one responsible for creation.

Saraswati: The Flow of Wisdom

At the heart of Brahma’s creative power lies Saraswati, his consort and embodiment of knowledge, music, and the arts. She is the river of wisdom flowing from Brahma’s silence, the voice of the Vedas themselves. Draped in white and seated on a lotus, Saraswati holds a veena (symbol of harmony), scriptures (knowledge), and mala beads (meditation).

Her name — a fusion of “Sara” (essence) and “Swa” (self) — speaks of accessing the very essence of one’s soul. With Saraswati beside him, Brahma doesn’t merely build matter — he weaves meaning into the fabric of existence.

Brahma’s Fall from Devotional Grace

Despite being the Creator, Brahma’s presence in active devotion is rare. Why?

- He has already completed his cosmic role — creation.

- His associations with desire and mistakes (like granting boons to asuras) cast him in a controversial light.

- Ancient curses from Shiva, following episodes of pride or deception, condemned Brahma to limited worship.

Only two temples in India, including the famous one at Pushkar, are dedicated solely to Brahma.

The Symbolism of the Form

Brahma’s iconography speaks volumes:

- Beard: Eternal age and timeless wisdom

- Closed eyes: Meditation on the Supreme

- Spoon: Role in sacrificial rituals

- Water pot: Source element of creation

- Vedas in hand: Perpetual knowledge

- Rosary: Reminder of devotion

- Mudras: Abhaya (protection) and Varada (boons)

Final Thoughts

Brahma is not just a creator — he is the first ripple in the still lake of the Absolute. Through him, Sanatana Dharma narrates a story of how form, mind, and rhythm emerged from the formless. Even though his temples are few, the idea of Brahma permeates every mantra, every ritual, and every philosophical contemplation.

To know Brahma is to recognize the moment where thought becomes matter — and silence gives rise to song.